Wrangling Redux - reducer size

Redux is not the 'new hotness'.

In fact, that it's probably quite far along the downward slope of the technology hype cycle. As far as state management for your average website goes, it's total overkill, as it introduces a lot of additional complexity for little concrete benefit. The learning curve is extremely steep, and you quickly feel like you're writing a lot of boiler-plate code to accomplish something trivial. Even its creator, Dan Ambramov, cautions one against blindly smashing redux into everything. In spite of these reasons, I have fallen in love with Redux. I am enamoured with the concept of 'Flux' architecture, as well as the lightweight implementation of the framework itself.

You have to understand that I come from a background of building scalable, transactional web applications, where performance and robustness are the highest priorities. These systems invariably led away from 'conventional' architectural models into 'event-based', functional (perhaps more function-ish) and distributed system models (queue-based / streaming / event sourced / whatever). A lot of the concepts that Redux is reliant on I feel come directly from this event-based world, or at the very least, I feel that a lot of the metaphors fit neatly into my mental model of how such systems work. Redux gives me the architectural constructs that I feel I need to turn the front end into just another node in a larger distributed, event-based system. It allows one to solve interesting problems, in interesting ways.

Excitement aside, this is not simply a love letter to Redux. There are many significant challenges to working with Redux, particularly if you approach it naively. It still has an incredibly steep learning curve, and a number of 'easy to stumble into' problems. Needless to say, I have stumbled into some of these problems, and I'd like to share some of my learnings.

The problem of objects #

Object-orientation is like one of those 4lbs hammers. You know the ones I mean; the masonry ones, of middling size, used for smashing bricks. It's a thing that can be used in a variety of situations, but isn't well suited for many of them. It doesn't break bricks as well as power tools, turns nails into a smear of metal against whatever you're hitting, and is pretty unwieldy and hard to use. The problem with it (both OO and hammers, I suppose), is that it's typically the first tool that you reach for in your toolbox. Let's look at an example.

We have to model some behaviour in a domain for learning management. We have tracks, courses, sections and users. The users can complete any number of sections, and any courses. Sections could belong to many courses, and courses could belong to many tracks. We want to be able to represent percentage completion of any given track/course based upon which sections a user has, well, completed. Anyway, this data has to come from somewhere, and you can easily fall into something like the following table structure*.

+--------+ +--------------+ +---------+ +----------------+ +----------+

| Tracks | -> | TrackCourses | -> | Courses | -> | CourseSections | -> | Sections |

+--------+ +--------------+ +---------+ +----------------+ +----------+

+------+ +--------------+

| User | -> | UserTracks |

+------+ +--------------+

| +--------------+

------> | UserCourses |

| +--------------+

| +--------------+

------> | UserSections |

+--------------+

*You get the idea, it's not meant to be a rigorous entity-relationship diagram.

When I looked at data structured like this, I represented this as a JSON tree with two branches and collapsed all of the 'linking' tables as being purely a database concern. In fact I decided that these two representations would be separated at a request level (two different http calls).

{

"tracks": [

{

"id": 1,

"name": "Web",

"courses": [

{

"id": 1,

"name": "HTML",

"sections": [

{

"id": 1,

"name": "Introduction"

}

]

}

]

}

]

}{

"user": {

"tracks": [

{

"id": 1,

"courses": [

{

"id": 1,

"sections": [

{

"id": 1

}

]

}

]

}

]

}

}I could then take an incredibly simple assumption with the reducer, and deal with these two trees as being objects on the state.

export const tracks = (state = [], action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case TRACKS_RECEIVED:

return [...action.tracks];

default:

return state;

}

};

export const user = (state = [], action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case USER_RECEIVED:

return [...action.tracks];

default:

return state;

}

};As much as this seems like an elegant approach, it becomes a problem very quickly (something that should have been clear from the nesting alone). The code becomes unnecessarily confusing and convoluted when you're required to traverse the object graph, such as in the following situations:

- Find and load a single section (for display on refresh),

- Mark a single section as complete,

- Show the percentage completion of a track or course.

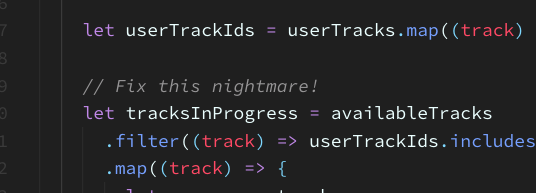

If you take, for example, the following piece of code that works out the percentage completion of a track. It bases the computation on its courses, or more specifically the sections inside that course. If a section has a userSection, then it is deemed complete.

export const selectInProgressTracks = (state) => {

if (!state.tracks || !state.user) return [];

let tracksInProgress = state.tracks.map((track) => {

let userTrack = state.user.tracks.find((u) => u.id === track.id);

let courses = track.courses.map((course) => {

let userCourse = userTrack.courses.find((c) => c.id === course.id);

let sections = course.sections.map((section) => {

let userSection = userCourse.sections.find((s) => s.id === section.id);

return {

...section,

...userSection

};

});

let progress = {

total: sections.length,

completed: sections.filter((s) => s.userSection).length

};

return {

...course,

...progress

};

});

let progress = {

total: courses.reduce((sum, course) => (sum += course.total), 0),

completed: courses.reduce((sum, course) => (sum += course.completed), 0)

};

return {

...track,

...progress

};

});

return tracksInProgress;

};Now... There are many problems with this code. It's deeply nested, and confusing to read through. It performs really (really) poorly, due to multiple iteration over the same array contents. The result be computed every time any part of the state tree updates. And even if we use memoisation to cache the results, we're going to see very little performance improvemnt. We could possibly write it a little neater, or make it a lot more performant, but it's very difficult to do both (trust me, I tried).

Turns out that this is a relatively common problem in Redux, which can be overcome by normalising the state shape. Like with so much in software, we stumbled across this solution ourselves without knowing what it was called. (I suppose this is where I pass some pithy comment about there being no new ideas?)

A side of reselect #

The selector example in the previous section is a relatively common pattern in redux. By encapsulating the state access behind a function, we can try and isolate our state tree from our component. This means that if we change how we access our state, it won't affect our component code, and it allows us to re-use the selector consistently across our application.

We can take this even further by using a library called reselect, which formalises this pattern with a few particularly salient features. It encourages removing duplicate (or repetitive) state out of the tree, by having the selectors be composeable. Something it accomplishes by memoizing the selector results. Simply put; if the input state for a selector doesn't change, it won't recompute the result - affording us with a nice performance bump.

It's highly likely that I'll post more about reselect again in the future, but for the moment it's important to note that it is heavily used in the solution proposed below.

Normalising the state #

So instead of directly translating the relational structure into an object structure, we can instead return something closer to the 'raw' data from the request. The only challenge we have is collapsing the linking tables (such as TrackCourses and CourseSections), as it is information we need. We end up with something along the lines of:

{

"tracks": [

{

"id": "1",

"name": "Web",

"courseIds": [1]

}

],

"courses": [

{

"id": "1",

"name": "HTML",

"sectionIds": [1]

}

],

"sections": [

{

"id": "1",

"name": "Introduction"

}

]

}And then respresent the user data, in a seperate request, as:

{

"tracks": [1],

"courses": [1],

"sections": [1]

}And this lets us transpose our two reducers into three, completely subsuming the user reducer.

export const tracks = (state = {}, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case TRACKS_RECEIVED:

return {...state, all: ...action.tracks};

case USER_TRACKS_RECEIVED:

return {...state, user: ...action.tracks};

default:

return state;

}

};

export const courses = (state = {}, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case COURSES_RECEIVED:

return {...state, all: ...action.courses};

case USER_COURSES_RECEIVED:

return {...state, user: ...action.courses};

default:

return state;

}

};

export const sections = (state = {}, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case SECTIONS_RECEIVED:

return {...state, all: ...action.sections};

case USER_SECTIONS_RECEIVED:

return {...state, user: ...action.sections};

default:

return state;

}

};So far there are no great shakes, but as soon as we take the next step we can see a marked difference in approach. We can now write selectors that handle each of the sections of our state tree independently.

export const selectSections = (state) => state.sections.all.map((section) => ({

...section,

userSection: state.sections.user.find((userSection) => userSection.sectionId === section.sectionId)

}))

);

const selectAllCourses = (state) => state.courses.all;

const selectUserCourses = (state) => state.courses.user;

export const selectCourses = createSelector(

selectAllCourses,

selectSections,

(courses, sections, user) =>

courses.map((course) => ({

...course,

sections: sections.filter((section) => course.sectionIds.includes(section.sectionId));

}))

);

export const selectAllTracks = (state) => state.tracks.all;

export const selectUserTracks = (state) => state.tracks.user;

export const selectTracks = createSelector(

selectAllTracks,

selectCourses,

selectUserTracks,

(tracks, courses, user) =>

tracks.map((track) => ({

...track,

courses: courses.filter((course) => track.courseIds.includes(course.courseId))

}))

);Now that might seem a bit confusing at first blush (see comments about learning curve above), but when you unpack it we only have a collection of really small functions that pick items out of the state tree. These functions are then individually memoised using reselect, and can then be composed to create really sophisticated selectors. Let's look at how we would do that using the in progress from above.

export const selectCourseProgress = createSelector(

selectCourses,

(courses) =>

courses.map((course) => {

let total = course.sections.length;

let completed = course.sections.filter((section) => section.userSectionId).length;

return {

...course,

total,

completed

};

})

);

export const selectTrackProgress = createSelector(

selectTracks,

selectCourseProgress,

(tracks, progress) =>

tracks.map((track) => {

let courses = track.courses.map((course) =>

progress.find((p) => p.courseId === course.courseId)

);

let total = courses.reduce((sum, course) => (sum += course.total), 0);

let completed = courses.reduce((sum, course) => (sum += course.completed), 0);

return {

...track,

total,

completed

};

})

);While they're not perfect, I believe that it's much improved. We now have a set of composeable, memoised functions that circumvented a lot of the problems in the previous example. Each individual selector is a simple function, or has a simple result function, that can be understood and tested in isolation. Without memoisation it is still not very performant code, but considering that Redux is built on a foundation of it, I feel that's a reasonable assumption to make.

Conclusion. #

There are, however, a few challenges to be aware of when turning your model inside-out. They primarily hinge around the fact that you don't have a single canonical model of your domain, and instead have to piece together your model from the actions, reducers and selectors scattered across your solution. As much as I'm not a big TypeScript fan, I feel like the reducer state would benefit greatly from having some guarantees as to what you can expect to be on the tree.

Nevertheless, when making this change we saw a marked improvement in the quality and complexity of the code in our solution. It wasn't all sunshine and roses; we were initially very concerned. Once we started normalising the state, we found we were adding quite a lot of additional (albeit simple) code in the form of our selectors. Some of them seemed so arbitrary, that they felt like they really had no place being refactored out of the component. We persisted, however, and then hit this watershed moment where we deleted large swathes of unsustainable code. In the end, all that we were left with was a few simple reducers and selectors, a result we were really happy with.